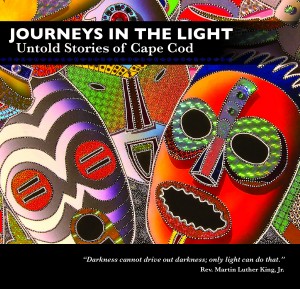

Journeys in the Light: Untold Stories of Cape Cod

Musings from the Filmmaker, by Janet Murphy Robertson

Musings from the Filmmaker, by Janet Murphy Robertson

Producing Journeys in the Light has been a personal journey and a joyful collaboration, an historical deep-dive and a much-needed check on hunches and biases I scarcely knew I had.

The Myth of Moral Progress

I once assumed that Americans came to a broader vision of “all men are created equal” as history unfolded, and that the exclusion of people of African descent in earlier times came from people not knowing any better. My assumption was incorrect.

The Mayflower Compact (1620) set down the goal of “just and equal laws…for the general good.” Quakers in seventeenth-century Cape Cod took a stance against slavery. Deep-thinking philosophers in Europe from John Locke (1632-1704) forward could find no reason to suggest a hierarchy of races to rationalize the rapidly growing practice of slavery.

And, later, abolitionist heroes like William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) and Prince Sears Crowell (1813-1881) were not really ahead of their time. They and their contemporaries – and, in fact, the majority of the country’s political leaders and general citizenry in the North and South – understood quite clearly that slavery was evil.

When you read the words of political leaders in various parts of the country right up to the Civil War, you can see that what was missing in America’s earlier days was not some better, contemporary view of right and wrong. Slavery was, in fact, known to be evil.

Africans were captured into slavery to fill the enormous demand for cheap labor in the Americas and, once slavery became entrenched, there was no collective will to disrupt the economy and social order by treating black people as equal to whites. Eventually, the Civil War was fueled less by moral outrage and more by competing visions for the country: one that valued individual states’ rights – including, even, the right to enslave other people – over the integrity of the Union as a whole – and one that would permit the federal government to curb states’ rights.

Professor James MacPherson of Princeton and others have written about this fundamental ideological divide in America since its beginnings and up to the present day. Early in the creation of Journeys in the Light, I became fascinated to learn more about the yin and yang of individual freedom and the common good, the role of heroes in the interplay of historical forces, and the historical roots of many present-day socioeconomic problems.

I came to understand why Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke of the appalling silence of “good” people and I discovered that my own personal heroes share two virtues: empathy and courage.

The Measure of Society

In his Federalist Papers, James Madison (1751-1836), traditionally considered as “the Father of the U.S. Constitution,” addressed another similar thread in American history, the tension between majority and minority rights.

In his own historical context, Madison considered “the majority” to be the masses of ordinary citizens and “the minority” to be the opulent landowners, but his point has general application. “It is of great importance in a republic, not only to guard the society against the oppression of its rulers, but to guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part.”

Majorities have power and can use it to favor themselves at the expense of minorities so, in a democracy that is pledged to freedom and equality, the treatment of minorities can be seen as a measure of the society’s moral caliber.

As I conducted research for the film, I became more and more aware of America’s shameful treatment of African Americans, as well as the extent of African Americans’ contributions to many important facets of America’s success throughout history – from agriculture and whaling to the military and all aspects of cultural life. The economic rise of the United States from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries was enabled by the toil of people of African descent from the cotton fields of Mississippi to the cranberry bogs of Cape Cod. And, all the while, African Americans were systematically deprived of educational opportunities, housing, voting rights, and more.

This all came alive for me as I spent months delving into the untold story of Cape Cod’s people of color and their ancestors. It might come as a surprise to you that my pride in America remained undiminished. This is because I came to a deeper sense of what makes America great and that is, specifically, its diversity.

It occurred to me that the true measure of a society is not only how it treats racial and ethnic minorities, but also the extent to which a society’s ideals, laws, and institutions inspire and permit its citizens to fight oppression. While the utopian vision of Plymouth Colony’s leaders was short-lived, the noble ideals did not die. They were even stronger and more powerful than the natural human greed and immediate self-interest of the majority. And they were kept vibrant and relevant by African Americans for whom the idea of a just and equal society was a solemn promise, which they used to argue skillful and ultimately successful cases within the U.S. court system.

The Importance of Being Factual

Many years after writing my last college term paper, I was reminded how crucial it is to read critically and choose sources carefully. I decided to rely heavily on the writings of American history scholars such as MacPherson and David Brion Davis of Yale. So much is written about the early days of America that is entirely false or, at best, misleading and I wanted to do my best to get to the facts.

For example, you can read in many places that the U.S. Constitution does not mention the word “slavery.” In reality, slavery was vigorously debated by the country’s early leaders and compromise was eventually struck between the slave and free states. Careful wording was included in the Constitution that protected the “peculiar institution” and the use of its proper name was deliberately avoided.

Specifically, it was agreed that the Atlantic Trade in enslaved people would not be abolished before 1808, that the slave population would be counted at the rate of three-fifths for the purpose of establishing Congressional representation, and that enslaved people who escaped into free states needed, by law, to be returned to their “owners.” It came as a shock to me that the Constitution explicitly countenanced slavery as an accommodation to the South and, intentionally or not, to the advantage of slave traders and textile mill owners in the North.

Again and again in history as noted by Hannah Arendt, Martin Luther King, Jr. and others, the inertia and silence of the majority of “good people” has enormous consequences. Issues left unresolved at the Constitutional Convention eventually erupted into the Civil War, and it was yet another century – well into my lifetime and that of roughly half of the adult population in the U.S. today – before African Americans attained the right to equal educational opportunities, the right to vote, and other fundamental freedoms. Much blood was shed once again in our country a mere half-century ago to achieve this.

Even to this day, much of this story of suffering and triumph in African Americans’ long struggle is left out of the history books. In my youth, what was noted was exclusively the parts of black or Native American history that intersected with the history of white people and, though school texts are more inclusive today, much of the story of people of color remains untold.

Elementary school children typically learn that Tisquantum helped the settlers and attended the first Thanksgiving, but not that he had been snatched previously from a beach on Cape Cod and sold into slavery in Malaga, Spain. We read about white abolitionists like Garrison, but little or nothing about earlier African American anti-slavery heroes like Thomas Dalton (1794-1883) or Charles Bennett Ray (1807-1886). We are taught about Booker T. Washington, but little or nothing about W.E.B. DuBois (1868-1963) who, a half-century before the Civil Rights Movement, co-founded the NAACP and demanded equal rights for black people under the law – far beyond Washington’s call for education and economic opportunity.

These largely untold stories matter, first, for people of color themselves, who are damaged and disrespected to the extent that their history is ignored. As Maya Angelou said, “there is no greater agony than holding an untold story inside you.”

And ignorance leaves us all prey to false narratives that would, for example, lay responsibility for the failure of Reconstruction at the feet of black people themselves, or fail to take with due seriousness the centuries-long deprivation of rights under the law that contributes to imbalances in the criminal justice system and other socioeconomic ills today. How are we to work for a better tomorrow if we do not understand the past?

Little by little, the broader and richer American story is being told, but there is push-back. I have heard people say with passion that American history should still be taught the way it was taught years ago. For some, a more inclusive story represents an assault on America’s iconic past. It is not, in my view, unless we lack a felt connection with people of a different skin color and continue to discount the importance of black lives.

Walking in the Shoes of Others

My own empathy got a needed boost as I worked on Journeys in the Light and collaborated with African American, Cape Verdean, and Wampanoag artists, local historians, and community advocates – many of whose families have made contributions to this country for far longer than mine, and who have committed a major portion of their lives, not only to advancing their own status, but to improving the lives of others in the community.

As I researched, interviewed, filmed, and photographed, the stories of extraordinary people past and present began to come into focus and I returned to an observation of my childhood. Isn’t it absurd for society to treat people differently simply because of the color of their skin? How would I feel if I were black? And, attempting to come to a better understanding, I used my imagination to picture what it would be like to be on the receiving end of racial bias.

I saw images of people much like myself everywhere as I grew up – in history books, on TV, on cereal boxes and billboards, and eventually in the faces of people who interviewed me for college and offered me a job. At least at a macro level, I was at home anywhere. I could walk into places where most everyone was anonymous at first – a playground or a movie theater – and later a real estate office or a polling place – and, whether I was welcomed warmly or not, I was never rejected outright and could likely accomplish what I set out to do.

I am white and have grown up in a predominantly white world and that automatically, merely in itself, gave me advantages vs. someone with a similar set of non race-related advantages and disadvantages who is black. This is indisputable. If I were black, my guess is that the biggest insult someone could send my way might be this: to deny that being white in a predominantly white society brings advantages. The reality is that, if it is hard for the average white American to get ahead, it is still far more difficult for the average African American to do so.

The Truth about the Social Ladder

In 1995, a Cape Cod boxer by the name of Kippy Diggs won the national and international welterweight championships. It was during the nineties that the first post-Civil Rights Movement generation came of age, and more and more star athletes, actors, doctors, and other professionals gained traction in careers and even celebrity status. In the year of Kippy Diggs’ triumph, the Million Man March also took place, in an urgent attempt to call attention to the stark disparities in income level, education, and many other indicators of success between blacks and whites.

I was struck by the contrast between Kippy Diggs’ big wins and the Million Man March, one sending the message that black people can achieve anything and one reminding us of the actual state of affairs. And I was reminded that the success of exceptional people with a good measure of luck says absolutely nothing about the opportunities for the average person. Nothing. Attitudes like, “He and she did it. Why can’t they?” are best seen in this light.

Here again, facts matter. Although the idea of upward mobility is part of the bedrock of Americans’ belief system, studies by the Brookings Institution and other organizations in recent years have shown that socioeconomic mobility is actually lower in America than in other comparable countries. And great racial disparities in education, healthcare, employment and other indicators still exist.

Building a Better Tomorrow

I find America’s history to be strikingly relevant to today’s national conversation about race. The high-stakes tug-of-war between two contrasting ideologies is currently playing out with no less vigor. Whether the issue is political correctness, affirmative action, gun control, immigration, or religion, the treasured American value of untrammeled freedom of the individual competes with the noble goal of the common good.

I have become convinced that knowledge of history can help us hold these two poles of the American psyche in balance. Seeing strong faith in people left out of the American social contract for generations, understanding how they transformed suffering into music and literature and created distinctively American genres respected around the world today, learning of the courage of the few in every era who have risked social isolation and even death to combat injustice – all this can free us from prejudice and connect us with our common humanity.

Digging into America’s past is an adventure. It empowers us to join in the national conversation armed with the facts. And I would recommend it wholeheartedly to anyone who dreams of an even better, more cohesive America.

Janet Murphy Robertson produced Journeys in the Light: Untold Stories of Cape Cod in collaboration with John L. Reed, Executive Director of the Zion Union Heritage Museum.

Her prior filmmaking credits include Icons of the Civil Rights Movement, based on the stunning art and historical exhibition by Pamela Chatterton-Purdy.

She is the Executive Director of ArtistsAndMusicians.org, a former executive with two major retail companies, and former President of the retail industry consulting firm Ogden Associates.

Click HERE to listen to Mindy Todd’s interview Janet Murphy Robertson on WCAI

Journeys in the Light: Untold Stories of Cape Cod

This new documentary film recounts the struggles and achievements of People of Color in this area.

Produced by ArtistsAndMusicians.org in collaboration with John L. Reed, Executive Director of the Zion Union Heritage Museum.

Funding provided by the Lyndon Paul LoRusso Charitable Foundation, the Mid-Cape Cultural Council, and the Town of Barnstable.

Click HERE to view the Trailer

The entire film can be viewed at:

Zion Union Heritage Museum

276 North Street

Hyannis, MA 02601

You can purchase the DVD in the Zion Union Heritage Museum store and selected other locations.